If you’ve ever tried to model glycosylated proteins, you know how quickly the visual landscape becomes crowded. When it comes to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, which mediates viral entry into human cells, the challenge is even greater: the spike is coated with sugars that play a protective role. Understanding how these sugars are arranged – and what they conceal or expose – is critical for antibody design and therapeutic targeting.

How do sugar molecules affect antigenicity? Why do neutralizing antibodies primarily target a specific region of the spike? This post summarizes a visually engaging section from the SAMSON documentation, focusing on the glycan shielding of the SARS-CoV-2 spike and offering visual tools for molecular modelers to explore this complex structure.

Glycan Shielding: A Viral Disguise

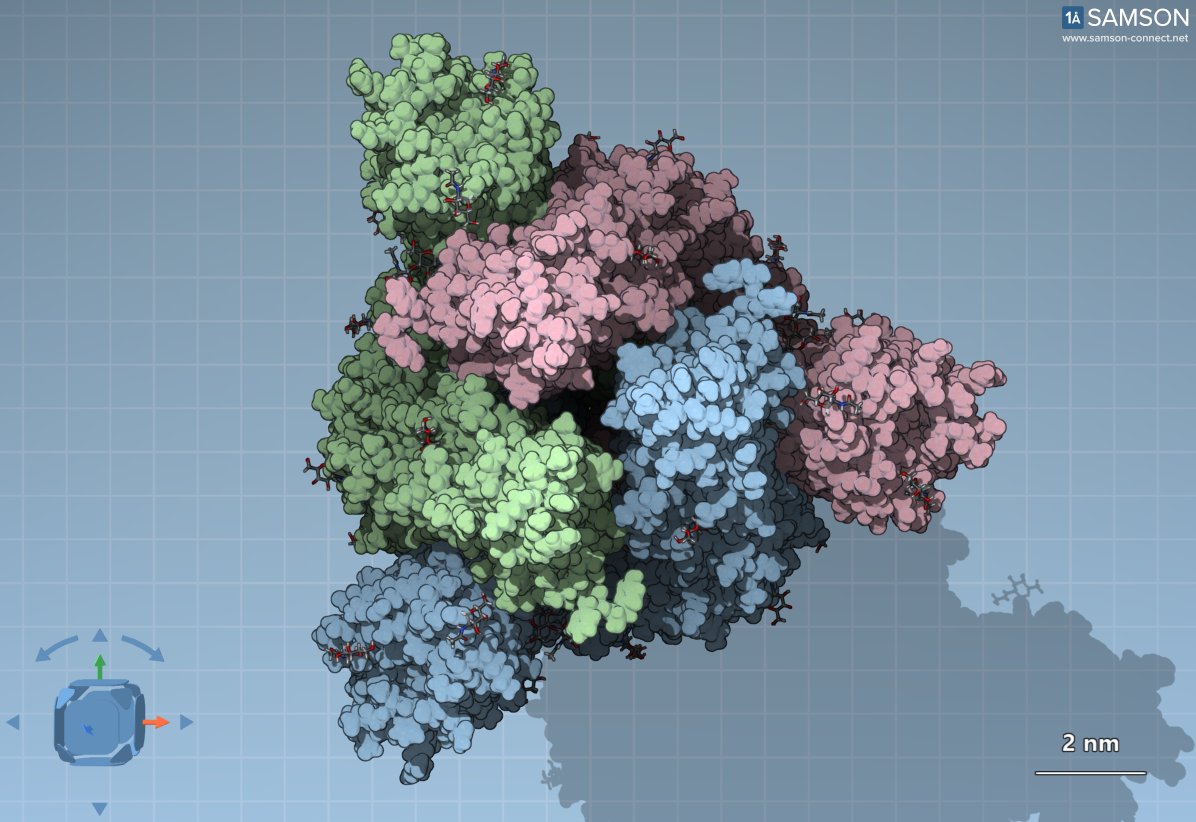

The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 consists of three S proteins arranged in a trimer, forming a structure with C3 symmetry. Each of these proteins is glycosylated — i.e., covered with sugar molecules. These glycans, visualized as surrounding clouds in molecular representations, act as a disguise to help the virus hide from the host’s immune system.

The top view of the spike in the closed state. Different colors designate the individual S proteins. The surrounding dots are sugar molecules (glycans).

The masking strategy is not unique to coronaviruses — HIV and influenza viruses also use similar approaches. Many cells in our bodies are coated with carbohydrate patterns, and our immune system learns to recognize these as ‘self’. By mimicking this coating, viruses can evade immune detection.

Crucial Exception: The Binding Site Isn’t Masked

Interestingly, not all parts of the SARS-CoV-2 spike are equally hidden. The very top of the spike — the receptor-binding domain (RBD) — lacks glycan shielding. This is likely because the virus must expose this region to bind to the ACE2 receptor on host cells. It’s a vulnerability: antibodies target this uncovered spot to prevent the virus from attaching and entering cells.

This insight is important for modelers and computational biologists developing vaccines or antibody therapies: visualizing which parts of the spike are accessible can inform the design of molecules that target viral weak points.

Tools for Better Visualization

SAMSON provides multiple rendering modes (Gaussian surface, secondary structure, van der Waals) and view angles (side and top) to help users identify key structural features.

Top view of the spike rendered in Gaussian surface (left) and secondary structure (right). Note the sugar molecules around the trimer interface, but not covering the RBD.

Pairing these views with downloadable molecular models lets you isolate the binding site, retrace antibody epitopes, or simulate glycan dynamics. Whether you’re designing biosensors or just want to better understand antigen exposure, these visualization tools give you a detailed, manipulable spike structure.

Conclusion

By visually dissecting which parts of the SARS-CoV-2 spike are protected by sugar molecules and which stay exposed, SAMSON helps molecular modelers focus their attention where it matters most — the binding site. If you’re researching antibody design or viral entry mechanisms, this distinction is critical.

To explore these structures and try the interactive 3D views, visit the full tutorial page.

SAMSON and all SAMSON Extensions are free for non-commercial use. You can download SAMSON here and start modeling right away.